"What fruitful dawdling!"

On Amtrak’s Lake Shore Limited. Chicago, IL. 9:43 p.m. Last Tuesday.

When I set off from my apartment some three weeks ago, I did so with a bag packed for a one-day work trip to Minnesota and a brief stop in my hometown of Holland for the Tulip Festival (I have never missed Tulip Time and living in New York will not change that).

Three weeks later, I have had and recovered from COVID (a second time), attended the Division III national ultimate frisbee championship, my sister’s college graduation, and Tulip Time (albeit isolated in my childhood bedroom). I have visited friends and family from Detroit to Chicago to St. Paul.

It seems that such an unexpected and — despite the plague — delightful journey ought to have a fitting conclusion. It is in that spirit that I find myself on Amtrak’s Lake Shore Limited which, on its journey of just over twenty hours, will carry me from Union Station in Chicago, across Indiana, Ohio, a sliver of Pennsylvania, and upstate New York, before running down the Hudson and under West 34th Street in Manhattan tomorrow evening.

In a stroke of excellent luck, I am traveling in a steeply discounted (but still criminally expensive) roomette, which consists of my own tiny sink and seating that can be converted to bunk beds. It is my first time in a roomette in well more than a decade, and I am reminded even before the bed has been made up that it is far and away the best and most sensible way to travel.

A one-way flight would be perhaps half the price and a tenth of the time of the Limited, but the train is worth it. A long-distance train ride is a special occasion, especially in the sleeper. In the lounge for sleeper passengers in Chicago, there are none of the characters you find in the airport. There are no diamond medallions boarding early. No business people argue about the x-ray signature of their shoe tree with the TSA. There are a few retirees, some Amish people, and a small child hanging about. Amtrak has set out some cans of Coke and a few bags of Skittles to lend some special flair. Mostly, the crowd is united by the idea that they’d like to go somewhere east at some point. Speed is secondary.

La Porte, IN. 10:45 p.m.

There is a distinct noise on a train when somebody pulls the emergency brake. It’s a loud hiss followed by a jolt as the great machine grinds to a halt. I know this from an Amtrak trip in Wisconsin when somebody thought they missed their stop, a high-speed train in France when the train hit an animal of some kind at 200 miles per hour, and a very long subway ride through Brooklyn. One hour and fifteen minutes outside of Chicago on the Lake Shore Limited is the latest addition to the list.

Usually, the power does not go out. This part of the experience is new, and it is unclear exactly why it has occurred. Nobody has explained the matter, and nobody seems particularly alarmed. It would be fine had the air conditioning not shut off.

Yesterday’s Limited ran on time. I checked and was almost shocked by the news. It is common for passenger trains to be held (illegally) behind freight trains by the freight railroads that own the tracks or for some other kind of drama to slow things down.

The Amtrak Alerts Twitter keeps a record of these delays. It is not a hopeful place. From the last three hours:

“UPDATE: Texas Eagle Train 22 which departed San Antonio (SAS) on 5/31 is currently south of Dallas (DAL) and is operating approx. 5hr late.”

“Sunset Limited Train 1, which departed New Orleans (NOL) on 5/29, is back on the move and currently operating approximately 9hr late.”

There is no mention of the Limited 30 minutes after our stop. There was briefly a hopeful creaking noise, but there was no movement as a result.

Mitchell, the attendant assigned to our car, confirmed that it was indeed the emergency brake and that “they are walking the train.” I am keeping an eye on the window, waiting for somebody to walk past with a flashlight, which happens in these situations.

“Do you know when the power will come back on?” asked a woman in the hall.

“As soon as they correct whatever the problem is,” Mitchell assured her.

A few minutes later, the train began a slow roll forward and the power kicked back on.

The train is still an hour from its first stop in South Bend, Indiana. Amtrak reports that it is 34 minutes behind schedule.

Buffalo, NY. 10:03 a.m. Wednesday.

The Coke and Skittles from the lounge and the general excitement of the whole journey kept me awake just past Elkhart, Indiana.

Going to bed on a train is a whole event. After the brushing of teeth is done, an instruction card outlines the proper method of bringing the upper bunk down from the ceiling, climbing the steps into which the sink has been folded, rolling into the bed, and fastening the safety straps so that you do not fall out of bed if the train makes a sudden movement.

The upper bunk has its very own window and curtain which means that, upon waking up in the morning, you can gaze out at the passing countryside and backyards and have the peculiar feeling of not knowing what time it is or which state you are in.

This morning, it was approximately nine and we — now ninety minutes behind — had just left Erie, Pennsylvania on our journey along the length of Lake Erie.

The first order of the day is cleaning up for breakfast, which involves the rather unique pleasure of showering at seventy miles per hour. It is among the greater speeds at which I, a person who does not usually shower at any speed at all, have showered. Apparently not expecting anyone to shower, Mitchell had stowed a checked bag in the dressing area of the shower room, but I worked around it, and by the time I made it to the dining car for my breakfast of French toast, I was feeling much less slimy.

Cleaned up and fed, I stepped off onto the platform briefly at Buffalo. Mitchell stood out next to the door in his pressed uniform, showing no signs of having slept and chatting with the conductor. A child who stepped off the train demanded, “Where’s the buffalo?” He seemed pleased to find a life-size statue of one in front of the station.

Minoa, NY. 1:17 p.m.

I was watching a movie back in the upper bunk when Mitchell came by to take lunch reservations. Two meals are included with the trip (three for those on the front section of the train that will split off in Albany and travel to Boston).

This route, when it was run by the New York Central Railroad before Amtrak took over American passenger service, was famed for its fine foods prepared from scratch in the dining car. (It also took only sixteen hours instead of twenty.) Amtrak maintained a respectable dining car service until somewhat recently when a jelly-spined killjoy former-airline-CEO executive transitioned most of the overnight routes east of Chicago to what he called “flexible dining” and what I call “airline food.”

To its credit, flexible dining does still include the option of eating in a dining car, though the food is not prepared from scratch. The spirit of the dining car, however, is maintained. Passengers are seated together at booths and strike up conversations while the conductor sits in the corner doing paperwork.

I sat with a visitor from Germany and with a veteran who had started his trip two days ago in Reno, Nevada. He grew up in New York, but now lives in Portland, Maine, and was headed home by way of Boston. He offered New England travel recommendations and we both spoke of our love for the Staten Island Ferry.

A couple from San Bernardino, California sat at a booth nearby on the way to their granddaughter’s high school graduation in New York. They spoke of the wonderful food in the dining car in the west, of eating steak with real silverware and drinking wine out of proper glasses. The baked ziti and meatballs in cardboard were good enough for what they were, but nothing like out west.

We stopped in Syracuse for a few minutes (still about an hour and a half behind schedule) and it started to rain.

The dining car is an endangered species. Amtrak, which is run by the federal government, is always under pressure to turn a profit. On the East Coast, where many trains each hour shuttle business travelers between big cities at exorbitant fares regularly exceeding those of the airlines, it is profitable. Trains like this, however, which connect great distances and the small cities in between, have not made a profit in years and are unlikely to do so any time soon.

Trains are a public service. It feels only right that New York and Chicago should be united by rail. Even so, only fifteen percent of travelers on this train will go from end to end like me. There is value in regularly connecting Elkhart, Indiana and Sandusky, Ohio with a train and, for this, the long-distance routes have remained.

The dining car, however, is politically trickier. To a joyless congressional hack looking for a shot at some performative austerity, the dining car must appear as a nostalgic indulgence maintained for the pleasure of a few good-for-nothing eccentrics. To me and the rest of the good-for-nothing eccentrics, chatting as we munch on our rolls and butter cakes, the dining car is an essential public service. It’s what we think of when we do our taxes every spring. It’s a special treat that makes life in this country worth living.

Albany, NY. 4:45 p.m.

The Boston half of the train left us here in Albany some time ago, leaving our half briefly without a locomotive, and thus without electricity or ventilation. The process of splitting the train and replacing the locomotive is scheduled to take more than an hour. Speeding the process along can make up time, and it appears that we will leave with a delay of only forty minutes, which is an improvement.

A long stop — or perhaps the lack of ventilation — has the effect of driving people out onto the platform. At this point in the journey, a cast of characters has begun to take shape. There are the people in the roomette across from mine, the people from the dining car, and the various train staff. Some have been the same since Chicago, though the conductors and engineers switch out every few hours along the way.

Years ago, when I refused to set foot on an airplane and made my whole family take the train for vacations (I stand by it), these long stops were called “smoke breaks.” The crew now calls them “fresh air breaks,” though it is unclear if this is a matter of preference or policy. The smokers on the platform do not seem to care either way.

The people who have been on the train all day seem to be in a leisurely mood. (If they were not in a leisurely mood and chose to take an Amtrak long-distance train, they would have been wheeled off the train in Cleveland with a rage-induced aneurysm.) One group chats with a sleeping car attendant, relitigating the dining car question and making comparative notes on French toast east and west of Chicago today versus thirty years ago. The fresh air break is a delight for a chronic overhearer:

“The Floridian! Now that was a train with fried chicken!”

“My brother got us all into this train thing. Now my mom’s been on every route in the country.”

“My auntie’s got some soup on the stove and I can’t wait! Come on, Poughkeepsie!”

A small crowd assembled to watch as a new locomotive was hooked up to our half of the train. They took many pictures of the workmen, who seemed indifferent. As the power kicked back on, everyone sauntered back to their rooms and seats.

On the platform in Albany, as everywhere, the train ride has a special sense of occasion. The new locomotive ushers in the evening activity: a sprint down the Hudson. It is a spectacle worth photographing and worth chatting about with strangers.

Nobody remembers a good flight. Air travel at its very best is unremarkable. Even the worst train trips, though, seem to have redeeming qualities worth talking about years later. It would be a challenge to remember anyone I ever sat next to on a plane, but I can still remember that my sleeper car attendant in eighth grade was called Stan and the man I had dinner with in a dining car in Texarkana in 2015 was headed to Philadelphia.

The platform was briefly filled with a small crowd of people joining the train for its last leg from Albany. To them, the train is solidly late. A few show signs of having spent the day engaged in the work of the State (the Capitol is just across the Hudson), and are wearing bow ties or buttons or t-shirts with policy slogans. They walk fast and seem to be living in an entirely different dimension from the long-haulers.

As the platform started to clear out for the train to depart, it began to rain again. In bedroom A, a mother shouted, “Quick! Quick!” to her children and they ran out onto the platform. “We’re from Arizona,” she explained to a few onlookers as her children spun around with their mouths open. “This is a big deal for us.”

New York. Later.

The trip down the Hudson, which feels on a short-distance trip like an event all its own, seems like a blip of a finale to a person who has already been on the train for nineteen hours. Anyone with the good fortune to be seated on the right side of the train has the great pleasure of watching boats and islands and West Point pass by and slowly change over to the New Jersey Palisades and the George Washington Bridge before the train slides into a tunnel in upper Manhattan for the rest of the journey.

Pennsylvania Station, which haunted travelers with its wretched subterranean passageways for decades following an act of callous architectural terrorism ill-advised mid-century reconstruction, has been largely replaced with the new Moynihan Train Hall. It is a beautiful, bright space filled with natural light occupying what was formerly a grand post office and a fitting way to enter the city. The building is named for Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who had shined shoes in Penn Station as a boy during the Great Depression. He later advocated for the new train hall in the United States Senate.

Moynihan, a train guy and a New Yorker, seemed to get it. The train is like New York. Both are too expensive, too unpredictable, and too difficult, such as to be almost unjustifiable. Sometimes the lights and the air conditioning shut off with no explanation. At the same time, they seem to be America at its best — democratic, improvisational, a little whimsical, and with a definite sense of improbably linked fate.

Few people check their bags on the train, but those arriving passengers who do see a quote from Moynihan over the baggage claim at his namesake train hall:

“In the old time, you arrived at Pennsylvania Station at the train platform. You went up the stairs to heaven. Make that Manhattan. And we shall have it again.

Praise all.”

Distractions

Things I have been reading, watching, and listening to this week.

The Axios Detroit Newsletter for May 24, 2022.

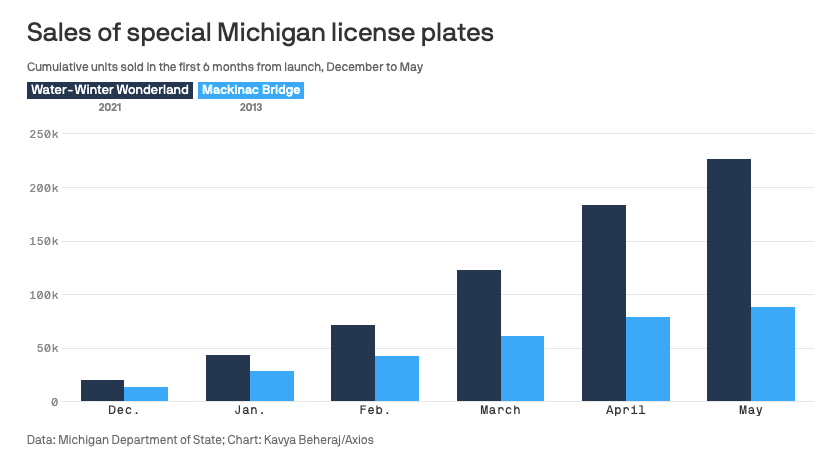

The morning after the previous edition of this publication, Axios Detroit did their own reporting on demand for Michigan’s new Water - Winter Wonderland license plates. (One must assume that they are big fans of the Newsletter.)

The verdict? I was right. The people love them! License plate replacement orders are double what they were when the last plate came out in 2013.

Flight of the Century on YouTube.

The New York Central Railroad produced Flight of the Century in 1935, detailing the marvels of the rail journey between Chicago and New York on the Twentieth Century Limited. Though it ran from LaSalle Street Station in Chicago to Grand Central in New York, the route was largely the same as today’s Lake Shore Limited (which is named for a different train also run by the New York Central around the same time).

The train feels unrecognizable today, with food made from scratch “for the tastes of people who are bred to gracious living” and an on-board barber. But the route is the same and the excitement over the whole spectacle is strangely familiar.

BONUS REPEAT: “The Railroad” by E. B. White in Essays of E. B. White or the paywalled New Yorker Archive.

“The Railroad” has made a previous appearance in this section of the Newsletter and, while I do not make a habit of repeating recommendations, I am doing so today. Writing on the night in 1960 that the last ever sleeping car from Bangor, Maine left for New York, White knew that trains were distinctly political and absolutely worth saving: “If Maine’s railroads are to stay alive and haul passengers, they will need help from villages, cities, the State, and the federal government.” They got that help (though perhaps not enough) eleven years later when Amtrak was formed to save what was left of passenger rail from the brink.

“A train on its leisurely course,” wrote White, “often reminds me of a small boy who has been sent on an errand; the train gets there eventually, and so does the boy, but after what adventures, what amusing distractions and excursions, what fruitful dawdling!”