I plan vacations by the book.

The Thomas Cook Group of London published their Thomas Cook European Rail Timetable for 140 years until, in August of 2013, they published their 1,526th and last edition, perhaps assuming that their customers would be happy to simply plan their journeys with websites or apps. To the people who buy timetables, however, there is simply no alternative. By October of 2013, the compilers of the Timetable had set up their own company. Thomas Cook collapsed in fall of 2019 and European Rail Timetable is on track to publish six print editions this year, so the compilers had the last laugh.

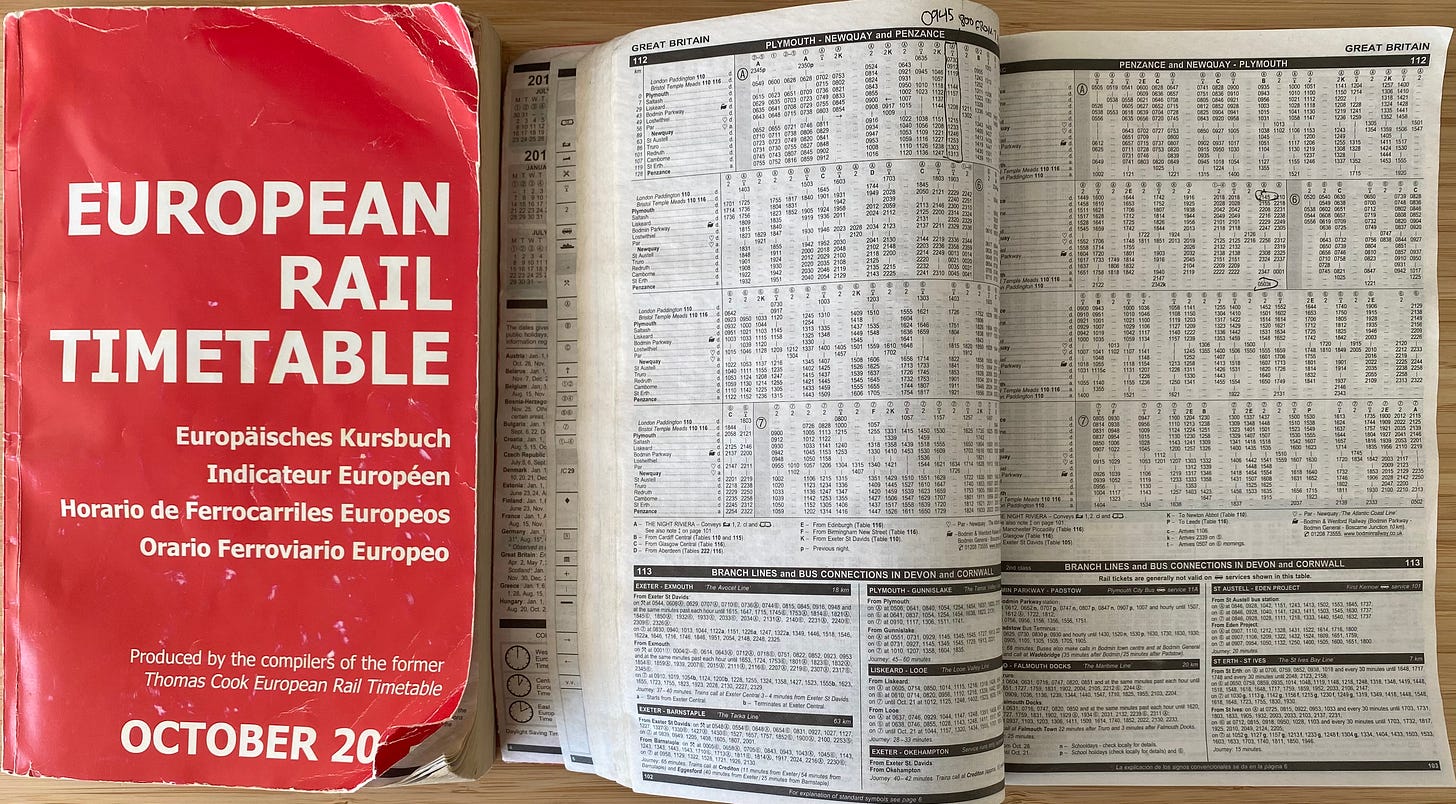

I am a proud owner of three such timetables. Each one memorializes a great train trip and is covered in the various scars of the journey. The covers are mangled from being crushed at the top of a backpack. The pages are dog-eared. The margins are filled with markings and notes on train timeliness and seat reservations. The fall 2019 edition has a tea stain on table 218, which details the workings of Scotland’s West Highland Line, and table 996 with hourly trains between Vienna and Bratislava is blotted with what I imagine was part of a pastry.

I was 16 when I got my first checking account and learned I could buy train tickets for myself. The gateway was the $46.40 deal (I remember the price distinctly) for a day trip from Holland to Chicago. Four years later, I developed a sort of obsession with finding cheap transatlantic airfares (the staple of which was a flight from Toronto to Reykjavík on an airline that has since ceased to be), and the age of the European Rail Timetable began.

It was not much longer before I figured out the promise of adult life: I spend most of the year scrimping and saving, drive a fuel-efficient car, avoid fancy restaurants, hoard my vacation days, wear a coat held together with duct tape in the winter, and try to keep the air conditioning off at night in the summer. In exchange, I spend a few weeks of the year pulling out all the stops on spectacular off-season train trips. This, to me, is an excellent deal.

The timetable book approaches 700 wafer-thin pages. Some are maps or travel advice or editorial bits from the all-knowing compilers. The rest contain the working details of 50,000 trains. “Needless to say,” the compilers caution, “it cannot be comprehensive. It would run into the thousands of pages.” (The book does contain a very comprehensive American section which clocks in at a tragic ten pages. Every rail service in Michigan, for example, is contained in table 9266, which is two inches tall.)

I usually order my copy of the timetable a month before my departure. Its arrival — along with that of the rail pass — is a momentous occasion. In a world of mediocrity and disappointment, the European Rail Timetable is full of endless possibilities. It is as if, for £17.99, you have been handed the keys to an entire continent of impeccable rail service.

Weddings, graduations, and births are all well and good. Certainly one cannot complain about such an occasion. These cannot compare, however, to the feeling of a long-suffering American with a fresh new timetable and rail pass in hand gazing up at a departure board.

Train travel is perfect. Nothing else compares. It is not a slower version of flying or a more expensive alternative to a bus. It is a pleasure all its own of low-speed, ritualistic charm. It is a unique experience in modern life to sit in a big chair with spotty cell reception and nothing to do while you stare out at forests and plains and mountains and backyards while a paper book determines where you stop and when.

I figure this is as much as a person could ask for out of life. I do not need a large house, a yard, or a television. My most earnest desire is to spend just a few hours out of the year gliding across some foreign land on a train eating while prosciutto and cracking the timetable’s elaborate code. So pleasurable is the experience that, no matter your destination, it is uniquely disappointing to arrive and to leave the train.

The October 2020 edition of the timetable is conspicuously absent from my collection. The last intercity train I took was in November of 2019 from Rotterdam to Schiphol Airport, where, two weeks earlier, I had rattled off a rail itinerary that elicited a look of horror and incredulity from the Dutch passport controller when he asked for our plans. The journey included six countries, 38 trains, one night on a boat, two sleeper trains, meetups with friends in ten different cities, and a total of 3,915 miles of rail travel (just ten fewer miles than the flight from Detroit to Amsterdam). Even if somebody had warned me that pestilence would soon strand all of us in our homes for more than a year, I cannot imagine I would have changed the itinerary.

The timetable is such a pleasure because a few brilliant Englishmen have taken it upon themselves to take the chaos of the world and condense it into black and white grids of 24-hour time with comprehensive notes and symbols that explain exactly what will happen anywhere on the European continent on every weekday, Sunday, and obscure regional holiday. Even they have not managed to crack the plague’s timetable just yet, but I have my fingers crossed for the expanded summer edition.

Distractions

Things I have been reading, watching, and listening to this week.

“The Railroad” by E. B. White in Essays of E. B. White or the paywalled New Yorker Archive.

Rail service in the United States is Not Good. It was not always this way. In this essay from 1960, White reflects on his love of the American railroad and laments its slow death at the hands of airlines, cars, and an indifferent government in his home state of Maine.

It may as well have been written today, on the first anniversary of the position of Amtrak CEO being passed from one mediocre airline executive and all-American Richard Beeching wannabe to another.

The wonderful pleasure of the dining car has been reduced to “contemporary dining” (code for boxed sandwiches in your seat for a fee) and the mighty western routes run only thrice weekly, but at least our public services are inching ever closer to the grail of profitability — even if it means the whole Amtrak system is reduced to a single charter bus between New York and Washington with fallout shelter nutrition crackers as the meal option.

White saw it coming sixty years ago.

“If Maine’s railroads are to stay alive and haul passengers, they will need help from villages, cities, the state, and the federal government, and I think they should get it. A state without rail service is a state that is coming apart at the seams, and when a train stops at a village depot anywhere in America and a passenger steps off, I think that village is in an enviable condition, even if the lone passenger turns out to be a bank robber who does nothing better than stir up the air for a little while.”

Night Mail on YouTube or from the British Film Institute.

Nobody does documentaries like the British, and this one from 1936 is an absolute masterwork. It follows the postal train that connected London with Scotland, includes an original score by Benjamin Britten and “verse commentary” by W. H. Auden, and is a perfect fusion this world’s two great pleasures: trains and mail.